"Quiz time!" shouts Maryjoy Heineman, as she moves a block of wood and a clamp to make room for herself at the construction table in her classroom.

Heineman, an Evanston Township High School mathematics teacher, teaches Geometry in Construction, one of more than 100 mixed-level courses offered at ETHS. These courses are the high school’s attempt to bridge the achievement gap between white students and traditionally underrepresented black and Latino students.

Listen to an audio story about the Geometry in Construction class.

At ETHS, mixed-level courses put regular- and honors-level students together in the same classroom, with the option to earn regular or honors credit.

A need for change

Although these courses have had a long history at ETHS, the school decided to fully implement its Restructured Freshman Year Initiative in the 2012-2013 school year by requiring mixed-level humanities courses for freshmen who scored above the 40th percentile in reading and a mixed-level biology course for all freshmen.

This move was a response to the overwhelming number of white students and the striking lack of students of color in honors courses, ETHS Principal Marcus Campbell said. According to an ETHS report, self-identified students of color represent a larger proportion of the student body than self-identified white students.

“Although we’re very diverse, the school has seen it as being problematic when you look at an honors-level course and it’s all white,” Campbell said. “And you look at a regular-level course, and it’s all majority students of color.”

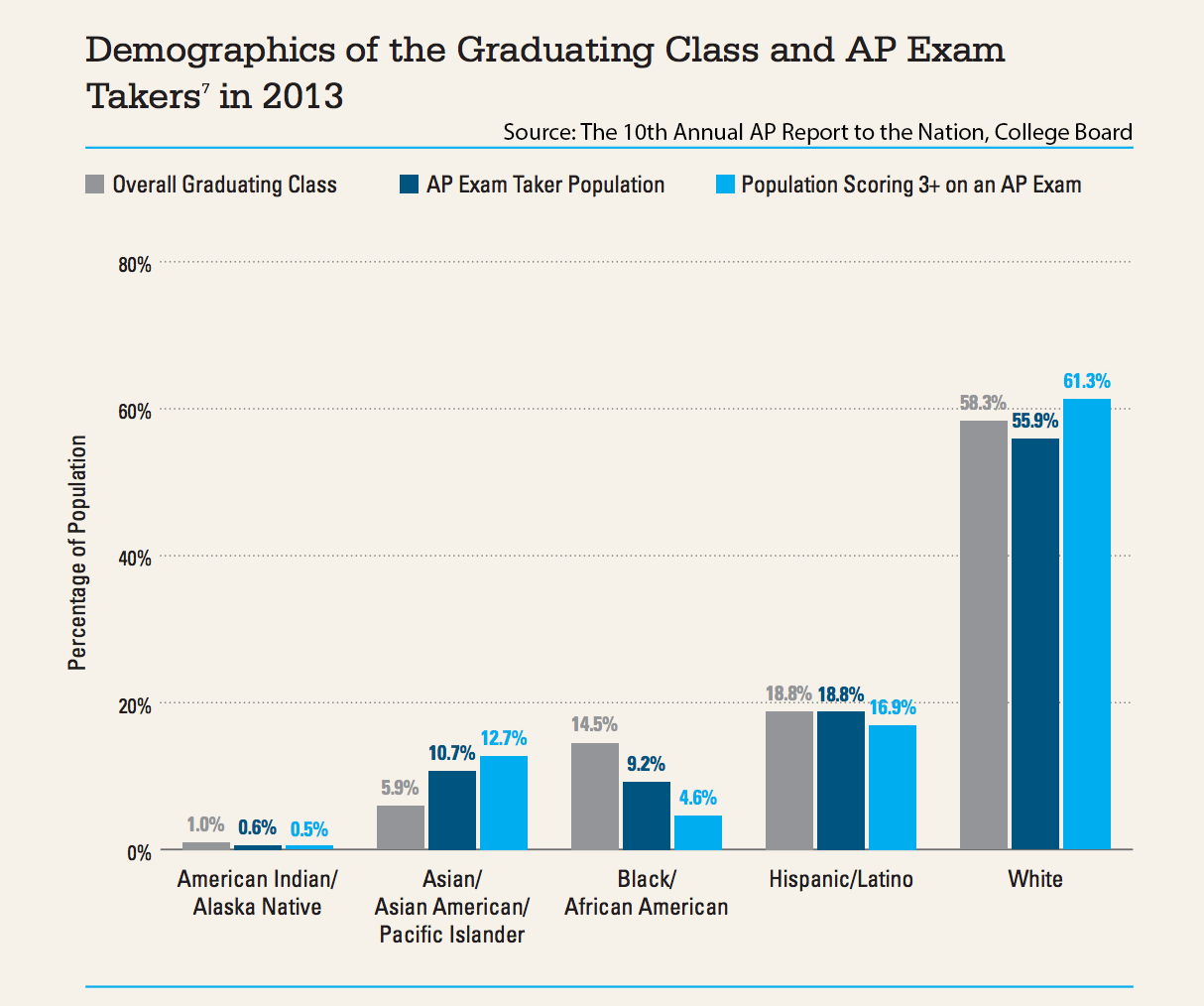

The achievement gap is not just an ETHS issue. A College Board report found the proportion of self-identifying white students who take or pass an Advanced Placement test is significantly higher than the proportion of self-identifying black and Latino students who do so combined.

Campbell hopes having mixed-abilities students share a classroom will encourage more students of color to pursue honors-level coursework.

“This is a way for us to encourage high expectations for all kids,” he said. “Not just for white kids, but all kids. That’s why we’re doing this.”

To mix or not to mix

The mixed-levels educational model is not a new concept; however, its implementation is still debated by education researchers.

Robert Slavin, the director of Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Research and Reform in Education, published in 1990 his findings on ability grouping in secondary education. Slavin found grouping had almost no effect on academic performance among students of varying achievement levels.

“There’s no evidence that (higher-level students) are harmed in terms of their achievement,” he said. “A high-achieving kid is going to be a high-achieving kid.”

However, potential problems with grouping arise, including an achievement gap. Slavin cited the concern of students of color not feeling up to the standards of more advanced courses. Consequently, they feel they don’t belong in those courses, he said.

“What (ETHS) is apparently doing is very sensible, by saying you don’t need to be in a separate class in order to have higher expectations,” he said.

Slavin’s stance draws concerns from others in the education field.

Susan Corwith, the associate director of Northwestern University’s Center for Talent Development, worries about the impact on higher-level students.

“The mixed-ability classroom isn’t necessarily a bad environment,” she said. “But it can be challenging, because (higher-level students) don’t tend to grow as quickly as other students in that classroom.”

― Marcia Gentry

Director, Gifted Education Resource Institute

Marcia Gentry, the director of Purdue University’s Gifted Education Resource Institute, had harsher criticism of mixed-level classrooms.

“I think it’s naïve to think that somehow by mixing the classes in a heterogeneous fashion that all kids are going to grow,” she said.

Care must be taken when addressing the achievement gap, she said. Her concern is that although mixed-level classrooms might address the achievement gap, it could adversely bring everybody to average.

“If you stop the top kids from growing, then you would reduce your achievement gap,” Gentry said. “But then everybody pays the price.”

"Wait and see"

Heineman, who has taught regular, honors and AP courses, is experienced with teaching to a diverse range of abilities. However, in her mixed-level classroom, Heineman said she has to lay out a more concrete foundation of the concepts before she can jump into the abstract, whereas she usually goes directly into the abstract when teaching an honors-level course.

"I feel like when I have a mixed-level course, there’s a little bit more in terms of me teaching students how to be a good student at the same time,” she said.

For successful mixed-level classrooms, Corwith cited the importance of “having strategies of support in place” for students.

“At ETHS, we’re fortunate because we have several levels of support,” said Pete Bavis, ETHS assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction.

One of those levels is AM Support, a 27-minute period before classes begin when students can get help from their teachers. Offered five days a week, it is built into every teacher’s schedule so students always have access to teachers during the time, Bavis said.

Despite having strategies of support, students still have reservations toward the change.

“(Teachers) have to teach to the honors student and the regular student in the same classroom, and that’s really hard,” said ETHS freshman Caleb Spalding, who is enrolled in five mixed-level courses. “Some kids in the (regular-level) don’t get it quite as fast as the honors students, so the teacher has to slow down. When my teacher slows down in biology, I get off task and it’s not good.”

Ultimately, the most important concern is whether or not the needs of the students are being met, Corwith said. Because the current freshman mixed-level model is relatively new at ETHS, the school has to “wait and see how it plays out with long-term objectives,” Bavis said at a school board meeting, according to the Evanston RoundTable.

Despite the debate surrounding mixed-level classrooms, Heineman appreciates the intermingling of ability levels.

“In preparing for this course, I knew going into it I had to teach it at an honors level and expect a lot from everybody, regardless of what level they have chosen,” she said. “I think it becomes a richer course for all of the kids.”